Service Navigation

What does Brexit mean for financial markets?

What does Brexit mean for financial markets?

The day after the Brexit referendum highlighted just how important a functioning market infrastructure really is.

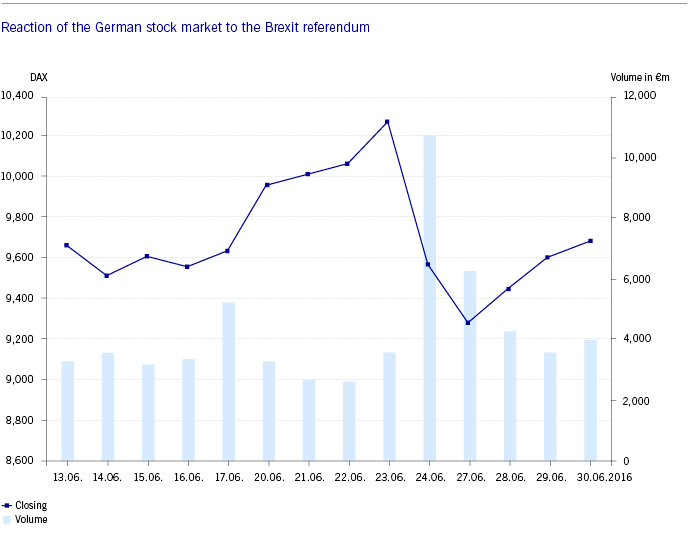

24 June 2016, the day after the UK’s historic Brexit referendum, saw Europe’s financial market legislation and supervisory framework severely tested. Trading that day was characterised by phenomenally high volatility and an extraordinarily high number of margin calls. About 2 trillion USD was wiped off the value of global stock markets in market conditions that were more turbulent than the notorious stock market crash of ‘Black Monday’ in October 1987.

Fig. 1: Performance of German benchmark index DAX® in index points and trading volume on Xetra® in € millions.

European market infrastructures and the legislative frameworks which regulate them, proved resilient and robust in the face of this extreme turbulence. Market safeguards, such as volatility interruptions and risk management by central counterparties, functioned exactly as designed at Deutsche Börse, ensuring financial markets continued to work smoothly and transparently despite the enormous volatility.

While Deutsche Börse Group very much regrets the UK’s Brexit decision, it is determined to make the best of the situation for the financial centres concerned and for Europe as a whole. Financial infrastructure providers like Deutsche Börse Group will play an important role during these uncertain times: they provide sound and stable trading and post-trade systems, which will be of invaluable support to clients as they adapt to the new post-Brexit regulatory and market environment.

Alexandra Hachmeister, Chief Regulatory Officer of Deutsche Börse Group, discusses the various Brexit scenarios which are on the table – from “soft” to “hard” and “cliff edge” Brexit.

Brexit in simple terms